Your donation will support the student journalists of Cresskill High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Getting Out of the Gauntlet: Cresskill’s Culture of Stress

June 17, 2020

It takes hold, so to speak, around four in the evening, just as the sun is bleeding out. It is slick—slinking in the overlooked corners—until, in the window, grim shadows descend over the weekend. It is a fraught hash of various malaises, each colliding and aggravating the other in turn. Shortly, it is the Sunday evening blues—that scramble of guilt, dread, despair, and gnawing anxiety that strikes before the looming workweek—and it is shared by a number of students at Cresskill High School.

On the surface, stress is easy to explain. Time-honored meme and paradigm, the “wellness triangle” is taken to be a tragic, inevitable framework for surviving high school: health, academics, social life—take your pick, wallow in it, but let the third edge sink.

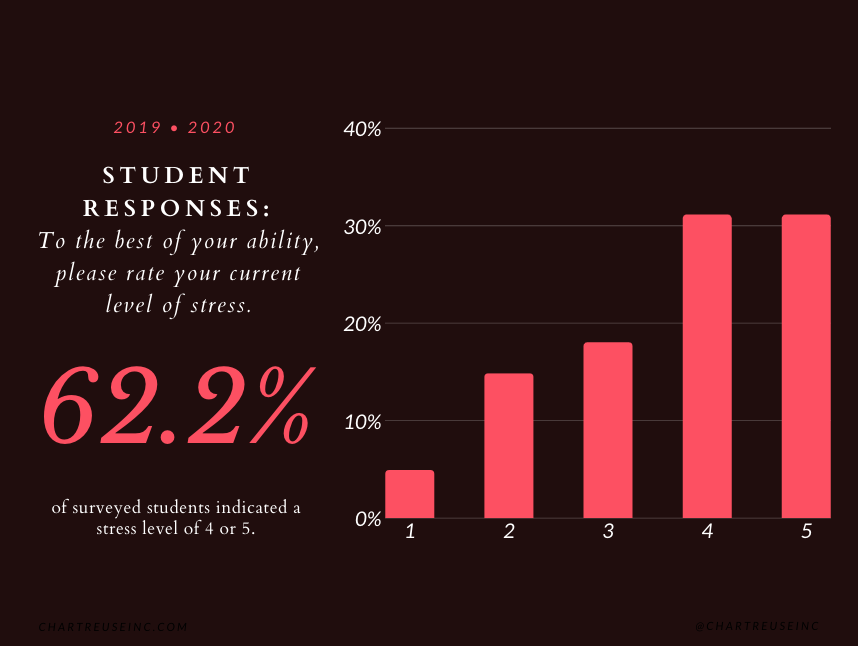

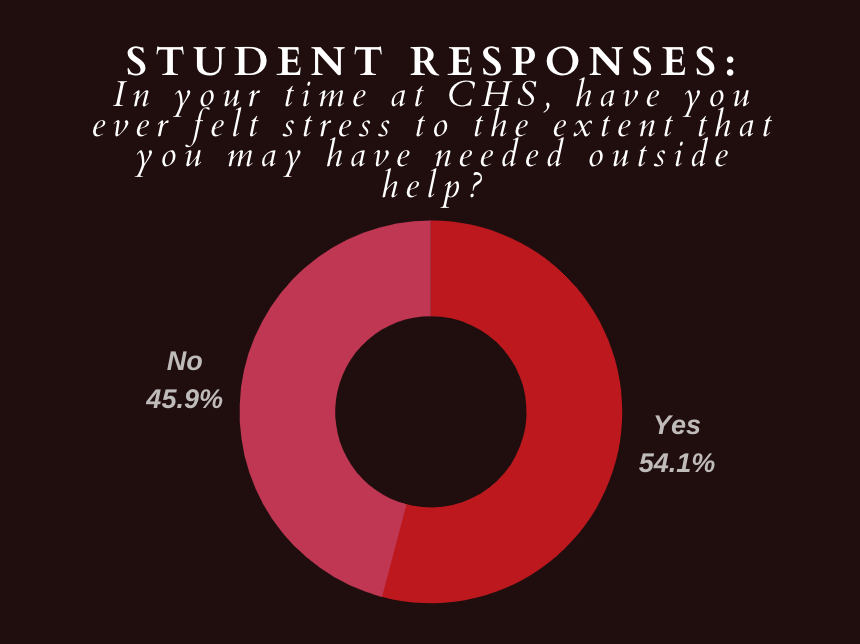

A survey distributed schoolwide in November 2019 offers some startling insights into the ways in which students experience stress at Cresskill. Asked to quantify their stress and provided with a 1-5 rating scale, over 62% of surveyed students indicated a level of four or five. Upwards of 54% of respondents, moreover, have felt stress to the extent that they needed “outside help.”

This essay’s aspirations are to scrutinize that stress, to excavate its roots, and to learn if a way out of it may be brought to light.

“Getting Out of the Gauntlet” first appeared in the spring 2020 print edition of The Communiqué. To view the edition in full, please click here.

✶

In the school day’s interstices, or in the snatches of time between bells, we might catch a line like this:

“I just failed the physics test—I got an 80.”

“I’m so dead. I got ten minutes of sleep last night.”

“That class makes me want to stab myself.”

“Kill me now.”

Laments like these, as well as the language of violence in which they are articulated, are fairly standard in Cresskill’s lexicon. The hyperbole, the fatalistic edge—the flippancy around grisly death—nobody blinks. Among classmates, we might deploy them as conversation fillers; among friends, we might trade them in greeting. In the discourse around stress, it’s become second nature at Cresskill to assume this parlance at some point in the day, students confirm.

“I hear statements like that countlessly,” says Haeun Park (‘20).

“You hear it a lot,” David Chu (‘20) agrees, “but you kind of rub it off and don’t really think too much about it.”

Students agree that Cresskill houses a competitive academic environment, but that it manifests in such quiet, unspoken ways as the vocabulary with which we discuss grades.

“It’s almost as if it is a competition,” says Sarah Loreto (‘20). “I feel like most students feel gratified or justified when [they are able to say] they’ve only gotten a couple hours of sleep because they were ‘studying,’” she adds.

To Nicole Huh (‘20), particularly statements claiming one has “failed” (when, categorically, one has not) is “a way we validate other peoples’ studying, [and] the way we validate our own studying.”

“I think that the student body is really competitive in the sense that people are trying to have the most ‘struggles’ to try and one-up everyone else,” says Lucia Park (‘22). “I really don’t like it because it just reestablishes really bad habits that could be bad for your health later on.”

“People compare their study habits with one another, and people get stressed because they feel like they’re not studying as much,” says David. “But I really do think it comes down to the fact that every person is different, and not everybody is going to have to study the same exact way, the same amount of hours, to study ‘hard’, quote unquote.”

“And I think we have very high standards,” Haeun adds. “I think comparisons are very much established in Cresskill’s study culture. The people who usually say ‘I failed that test’—even though objectively speaking, an 80 is not a bad score—may not actually think that they failed it, but rather want to give off the feeling that ‘I have infinite potential; I can do so much better than that.’”

For Sarah, the toxicity of this kind of language soon crept into the ways she assessed her own study habits and dampened her satisfaction with her academic performance.

“[In junior year,] I would often be unnecessarily stressed because I didn’t want to perform worse on an assignment than my peers and my friends,” she recalls. “As everyone compares their grades with one another, I felt obligated to do well to prove myself, and that led me to feel more stress than I should have.

“Every student feels stress at some point in their life,” Sarah reflects, “and I feel like instead of talking about how much you are stressed, there should be more conversation on how to deal with that stress.”

Evidently, language, even the sort that is slung around unthinkingly to fill our awkward silences, is hardly inert. And there is a perilously undervalued power in suggestion.

✶

At any rate, this culture is hardly unique to Cresskill. Junior Raymond Leu, who transferred to CHS in September, suggests that the issue is far more universal.

At his former school, Raymond found himself hemmed in at all sides by a suffocating culture of comparison.

“There [were] a bunch of unreasonable academic expectations. And if you buy into them, then it’s a vicious cycle,” he says. “What you end up having is very, very stressed kids who will turn to anything to get rid of that stress.”

In particular, coping with stress at Raymond’s former school manifested in such forms as cutting class, self-medication (by way of “drinking, stress-eating, and drug use”), and, much like at Cresskill, the language with which students spoke about academic life.

“It was expected at my old school—you’re supposed to complain about your test grades; you’re supposed to say, ‘I’m cooler than you because I only slept for 20 minutes yesterday,’” Raymond recounts.

“The thought there [was] that ‘in two years when I apply, these are the people I’m competing against for college, so I must put myself above the crowd,’” he explains. “So if I help you, I’m making my chances worse.”

This attitude virtually isolated students in their study lives, making it “a very shameful thing to ask for help from friends, because asking meant you weren’t as good as them,” Raymond recalls. In an environment that pitted classmates against one another and rendered friends furtive rivals, stress and isolation bore heavily on students’ mental health—whose few outlets were, as with seeking homework help, steeped in toxicity.

“I think part of the reason I had a bad experience at my old school was that I couldn’t cope with the stress,” Raymond speculates. “Having an open conversation about [stress] with [my former classmates would] get your reputation canceled. They [would] spread it; they [would] say, ‘Oh, this kid can’t handle it. He doesn’t belong.’ So even if I did talk about it,” he reasons, “I don’t think that the people there would’ve understood me or expressed any sort of sympathy.

“You couldn’t tell anyone about it,” Raymond adds, “because if you told the intellectual people, they’d be like, ‘Oh don’t worry about this class—all you have to do is this and this and this.’” On the other hand, “if you [talked] to the ‘bad’ kids, [they would] just say, ‘Oh don’t worry, I did worse than you on that.’”

The paradox of reaching out testifies to how competitiveness has the potential to swing toward either extreme. Even as students strain to outperform each other in academics, they simultaneously strive to maintain a semblance of hardy mental health, distancing themselves from the stain of tryhard status. They outdo in caring less.

At this impasse, Raymond found himself associating more with “so-called ‘bad’ kids”: “It made me feel good about where I was even though I shouldn’t [have],” he confesses. “I was not in a good place, so I surrounded myself with those people. And it made me feel good that they could come to me for help and I didn’t have to go to anyone else, but that made sure that I didn’t improve at all in anything.

“If I was given one thing that I could’ve changed about my career at my old school, I would tell myself, ‘I know you think that you’re handling the stress right now, but you legitimately need help right now,’” Raymond reflects. “And coping with stress is just looking for help.”

✶

What of that other, darker breed of statements—those that threaten, by any number of means, death?

Suicidal memes are ubiquitous across the social media platforms populated by high school-aged students, evident in the hashtags devoted to such memes’ diverse subgenres, and in the Facebook groups—boasting thousands of members—that oversee their wholesale exchange. Ostensibly, there is good work being done: in making light of a long-taboo topic, memes certainly subvert the stigma surrounding mental health. But there is something to be said for their characteristic irreverence, which, as detractors contend, risks trivializing suicide, as well as their tendency to normalize suicidal talk to an excessive extent. One aspect is beyond dispute: they obscure whether or not the sentiment is truly meant.

Amongst high school students, I want to die and its tangential iterations no longer carry any gravity. Language that flirts with notions of suicidal ideation has lodged itself so deeply in high school culture that students don’t as much as bristle at it. Desensitized, no one pauses to ponder the possibility that someone’s muttered kill me now might be, sincerely, an entreaty for help. It is a grim prospect: that when one makes their way out of the pit just enough to tell someone, they get shrugged off. And it speaks volumes for the dire need of a greater dialogue around mental health.

“For many of us, it takes a lot to voice the need for help—to say, I’ve been feeling really alone and empty and without purpose,” Jane (‘20)* says. “We’ve never even been taught to vocalize it, anyway—forget how,” she adds. “Come to think of it, that might be a better use of Health Class.”

Indeed, Cresskill’s program of studies doesn’t allot much space for students to learn about mental health, much less to receive training on how to properly communicate emotional needs, as the Health syllabus currently comprises First Aid (ninth grade), Drivers Education (tenth grade), Human Sexuality (eleventh grade), and Family Living (twelfth grade). The curriculum’s priorities seem sharply disordered, especially given that students themselves express that mental health is of pressing significance.

“Mental health is thrown under the rug,” says Nicole. “Something needs to be done.”

Haeun agrees. “Stress, I think, has become such a commonplace thing that no one takes any notice of it anymore,” she says. “It’s a perpetual state of stressedness.”

“At 15, 16, 17, you don’t know what’s normal,” Nicole adds. “Some people might have a mental health issue and might not even realize it. They might think it’s normal when it’s not.”

Nicole’s sentiment resonated particularly with Haeun, who found herself mired in “a state of constant stress and pressure” during her junior year, one whose effects have lingered even in the second semester of her senior year.

“I still have a hard time sleeping at night sometimes,” she confesses, “because I feel so chased by time and the knowledge that I have yet to achieve my end goal, whatever that is.”

Reflecting on her junior year, Haeun is reminded of the comorbidity of chronic stress and a persistent feeling of apathy, recalling, “At a certain point, I became very numb. I don’t think anxiety and depression are the only things that you should watch out for—on the contrary, a more pressing issue is just the state of numbness. But I don’t know if there’s a name for that, and I’m not a psychologist.” She adds, “I haven’t actually gone to a therapy session, so I’m not quite sure if I have any mental issues, or if what I’m feeling is just normal things that every student feels.”

Haeun’s experience speaks to how there isn’t merely a lack of literacy in how to communicate for help. The basic prerequisite to communication, a recognition of when to reach out for help, calls for self-awareness and a mental health education that Cresskill fails to provide. Students have no means of gauging their own wellbeing, and thus aren’t educated in self-monitoring—in proactively looking for and picking up on signals indicating they have dipped below mental wellness—and understandably so, when stress is the unquestioned norm at Cresskill.

Stress has tucked itself into a staticky backdrop. This doesn’t mean we’ve succeeded at learning ways of coping—rather, we’ve learned ways of suppressing its less light-hearted expressions, contorting stress into humor and vernacular while it rankles all the same behind closed doors.

“Someone’s first attempt at reaching out becomes their last,” Jane reflects. “That is terrifying.”

✶

In the guidance office’s central hallway, an outsize sign arrests the eye. There, in a bold serif: Senior Future Plans, it reads. Beneath it, crisp black lines have carved a sprawling tabulation out of the row of six whiteboards lining the wall. They delineate the names of colleges in alternating Expo colors, and beside these, tally marks denote the number of students who have been awarded acceptance.

Last year, things were slightly more specific—in particular, students’ names were disclosed adjacent to the schools to which they’d been awarded acceptance. This year, though, Guidance granted seniors a new layer of privacy, changing the format to retain students’ anonymity (and, as students tacitly understand, to save face for students and school alike).

The question of whether a board should even exist is somewhat of a fault line for students.

Audrey Cho (‘20) suggests that the board should be eliminated altogether, pointing out how it “adds to [students’] pressure.”

“Where anyone gets into shouldn’t really matter,” she says. “I think it promotes people being nosy and creepy, and that’s none of their business.”

Jane agrees. “When you went into the Guidance Office last year, there was always a group of kids gawking at the wall,” she says. “Everyone knows that what they were really doing was comparing the seniors, making judgments about who was smart based on the schools someone had been accepted into.

“But you honestly can’t blame them,” Jane allows: “it’s just so juicy.”

For Nicole, the board’s significance changed from year to year.

“As an underclassman,” she recalls, “it was really informative as to who to ask—I didn’t stress out about it then.”

But things quickly changed when her turn rolled around.

“The fact that I was going to be up on that wall, too, didn’t really hit me until the beginning of senior year,” Nicole admits. “Then I began to stress about it a lot.”

However, Nicole feels that this year’s changes have constituted an improvement. “I feel like it’s a lot better that it’s anonymous, but you still have the colleges up, so that it’s not just for the seniors to see, but also for the entire school to see,” she says. “I appreciate that there is a board.”

Junior Janice Kim, on the other hand, has always been attuned to the implications of a board that showcases acceptances to such a public extent.

“The fact that we’re getting judged by all these people based on which schools we get into it [is] very overwhelming,” she says.

But Janice acknowledges that the board has value as a source of information as well as a physical token of the payoffs of students’ hard work.

“As a junior, I’m really curious as to how the seniors are doing,” she explains, “because I have friends who are seniors right now. And just as a student, it’s really nice to see how Cresskill is doing really good, people are getting into a lot of colleges—something to be proud of,” she adds. “But at the same time, once you reveal the name [of the student], it’s kind of losing its purpose.”

Ultimately, students can agree that this year’s changes are a step in the right direction, in that anonymity discourages the tendency toward using the board for comparison.

But in dismantling Cresskill’s culture of comparison, is the gesture too little, too late?

✶

Guidance aspires toward achieving “a model which focuses on the needs of the students in three areas of development: academic, career, and personal/social,” as per the 2019-20 Student Handbook. The obligations of Cresskill’s Guidance Department extend beyond academics alone, to the personal spheres of students’ lives—including, surely, mental welfare. Yet, given the staggering proportion of students who experience stress to an extent that demands outside help, guidance services are pronouncedly underutilized. In a schoolwide survey conducted in late 2019, when asked about where they seek help, only two respondents listed the Guidance Department or the school’s child study team as sources.

With resources at their disposal, why aren’t students putting them to use?

“I think the level of work that is placed on the guidance counselors makes it so that they don’t have enough time for individual talks,” George (‘20)* volunteers.

If this is the case, then the situation should make for an easy fix: expanding Guidance personnel. But George espouses a more cynical view: hiring more counselors doesn’t suffice as a solution because it misses the heart of the issue. Regardless of potential expansion efforts, George says, “I know this sounds really sad and bleak, but I think there will always be an issue of not having enough time.”

Seeking help from the guidance department is necessarily a two-way street. While Guidance ought to make an effort to be reliably accessible, the act of going to Guidance ultimately lies with students’ agency.

But the trouble with Guidance is apparently twofold—beyond mere availability, there seems to be an assumption that going to Guidance is entirely fruitless, as well as an air about Guidance that students find forbidding.

Sarah opines that the initiatives Guidance has organized in past years have been entertaining at best.

“I don’t really believe in those whole big mental health movements that a school will do,” she confesses, “like ‘mental health week’ or some other bogus event. Sure it was ‘fun’ [walking] around the gym collecting stamps, but it didn’t change anything.”

Jenna (‘20)* contends that there is a general attitude of wariness toward Guidance’s initiatives, which blunts their impact.

“I don’t think a lot of students trust their guidance counselors,” she says.

Sarah adds that beyond trust, which is tough to quantify and tougher still to earn, the initiatives fall flat because the drive behind them isn’t sustained for nearly long enough, which ultimately conveys inauthenticity.

“The school will pretend that mental health is such a big deal and show it through these cheesy events,” Sarah says, “where in reality, the students don’t even care. Most [are] just trying to get it over with without engaging. You have this hype, for let’s say a week or so,” she explains, “but then it goes back to the same thing. That’s because it’s not an issue that should be hyped for one day and then ignored the next.”

Moreover, George admits that he has yet to feel that Guidance “is very comfortable or warm or welcoming,” acknowledging the generational differences that exist between Guidance and the student body: “Bluntly speaking, I think some guidance counselors can be very insensitive, especially because they’ve probably never gone through the experiences [that students are currently going through,]” he says.

Jenna posits that this disconnect has much to do with students’ impression of Guidance. She suggests that the image that Guidance has crafted for itself communicates to students that it is focused on the academic realm of students’ lives—college in particular—above all else.

“A lot of the staff just assumes you’re stressed about your grades,” Jenna says, “and a lot of guidance counselors assume that students aren’t struggling outside of academics. I feel like they’re just there to get us into college.”

“Guidance kind of depicts itself as the go-to for everything college-related,” Jane adds, “and college is linked to stress. So the bad vibes of that spill over into Guidance’s vibes, and ‘Guidance’ gets entangled with ‘stress.’”

“Go-to” is a fairly accurate descriptor. In all things scheduling, transcripts, visits, recommendations, and college planning broadly, Guidance has made itself the nucleus—at the expense, it seems, of other crucial focuses.

What, then, can be done to close the distance?

Sarah suggests a gradual approach, beginning with a basic provision.

“I just say pay attention,” she says. “Actually recognize how the students are feeling and consider their stress. It takes time and consideration to make change, so if anything, just pay attention.”

Conversely, Jane feels that Cresskill needs to embrace more immediate measures.

“This is kind of a big change,” she concedes, “but I’d honestly feel a lot more at ease if some guidance counselors were designated for mental health only, and others for college apps or academic help.”

Though drastic, such a change makes sense in light of the problem at hand. In students’ eyes, Guidance in its present state is intimately tied to the maddening work of getting into college, and to extricate the two, the administration may do well to compartmentalize Guidance’s distinct, non-academic functions. Demarcating Guidance’s academic and mental health arms by counselor would make for a meaningful separation of what ought to be stress-allaying—namely, a Guidance that assists in issues of mental health—and what is, inescapably, stress-inducing.

✶

It is like this sometimes.

The yawn and the give, the happy slowness of things. The dawdling schedule you can really do without. The small fluxes of daylight, here and there, and the languorous day—slacking.

It strikes senior year, in the flush of January—or February, at the latest, juddering to a start. Maybe in a little lull in the workflow—maybe not. Sunday lapses into the grind of the workweek, but nothing seems to turn. And it is frustrating—how, however you try, you can’t propel yourself from bed. That intellectual hunger—the one on which fervid application essays were penned—flickers out. It is really a kind of numbness: you don’t feel the crunch anymore. As if it were there one day and then not.

Academic disengagement amongst second-semester seniors is readily shrugged off as an inevitability of the pressure cooker of high school. Its cutesy moniker—senioritis—suggests the same. But one need only peer beyond the shiny veneer of that and a grimmer reality unfolds, one glaringly evident in how the college craze consumes senior fall.

On how her study life has changed from junior to senior year, Nicole says, “Junior year was a lot about doing well, getting that test grade. As a senior, I don’t care as much about grades; it’s more about getting college apps done. The focus shifts,” she concludes, “from grades and test scores onto essays.”

This is what many know high school to be: not as the site of education, but rather of honing each component of the college application. The disproportionate focus on college has taught students that high school is but an intermediary—a stepping stone on the winding path to college.

Moreover, the college craze is, it seems, all-consuming to the extent that it supplants in-school learning in importance. This is as evident in the time allotted for each commitment as it is in the mental real estate carved out for the same.

Josh*, an alumnus of CHS, recalls a similar order of priorities during his college application experience.

“When I got back from junior summer, it was almost as if everything was cleared out for me to prepare for college,” Josh recalls. “I guess things worked nicely, because it was college application season, and college [had] been my goal—my long-term goal—for so long. School wasn’t important.”

School was hardly the only aspect kicked to the wayside in the trek toward college. Josh had studied the wellness triangle, surely, or come to understand intuitively that sacrifices had to be made. In the tradeoff for single-mindedly pursuing his studies, Josh elected to let his social life languish.

“To be honest, high school was just a disaster—it was like a hundred pounds of junk and [expletive],” Josh says, “and all the other stuff made it so much harder to focus and get my tasks done. I didn’t get to make friends or whatever… but I did end up with pretty decent grades.”

Josh’s abidance with the dictates of the wellness triangle seemed to pay off in the end. That fall, he would apply under Harvard’s Early Action program and gain word of his acceptance in December.

Evidently, high school students feel they are taught to hurtle toward one objective: college. Those who take this end to heart thrust themselves into a grueling process that begins long before the fall of senior year—surely, if Guidance, as well as those private college consulting agencies so prevalent in Bergen County, present freshmen with “college roadmaps” from the outset of their high school careers. Once acceptances roll around, students have little motivation left to keep the grind going for school—and why should they, when they’re, once and for all, “in”?

Josh’s story provides further insights.

“I was so focused on the college app, and applying to Harvard; that’s how the fall went by,” Josh recounts, “and the spring of senior year was a little slower.”

More specifically, the spring took on a deadening lethargy that made everything feel a little askew.

“Most of the time, when I was sitting in class, I felt like I was in the wrong place,” Josh recalls. “Senior year was easy, but something was not right. Maybe it was because I was accelerated in math, but it felt like one year where I was waiting, waiting for college, but for some reason I had to get through another year of high school.

“To be honest,” he says, “I can’t believe I actually graduated sometimes.”

✶

We think too little of senioritis and the ills latent beneath its innocuous sheen. That getting into college chafes against true learning is telling of a deeper poison in our system. Rather than self-discovery, self-examination, and the various other processes undertaken to prepare for adult civic life, it is as if high school’s culminating moment has been whittled down to one: the college application. Students’ understanding of high school has deviated alarmingly from its intended thrust, and in turn, senior year has been cheapened into a period of interlude to move idly through as we wait afoot for college. Senioritis speaks to a failure of our education to instill in us a real value for education. When we don’t have such values secure, we crash. We burn out. We advance through the years without a sense of what we want, our eyes forever fixed on the outcome and not the process—the path that led us to it.

How do we break out of the mindset that primes us for senioritis?

It’s useful to look over our shoulders a little, to the history of the process that seems to maintain a stranglehold over students’ priorities.

Around the turn of the century, colleges loosened the emphasis on cold hard figures and lent greater weight to extracurricular activities, overhauling their GPA-centric approach to admissions in favor of a so-called “well-roundedness.” In theory, extracurriculars would speak to the softer, more nebulous dimensions of character, leadership, and personal integrity.

In effect, the change magnified the influence of the admissions juggernaut, bearing it beyond the classroom and the testing center into students’ daily lives. What was to be a humanizing change quickly turned numerical in practice, as such qualities as “personality,” as was exposed in Harvard’s 2019 admissions lawsuit, are ultimately boiled down to scores, too.

Often bolstered by vigilant parents, students who set their sights on lofty universities disperse their time between different iterations of token work, later to be surgeried together into window dressing for applications. They wring out what personal advantages might proffer an edge: take bloodlines, for one, which bind legacies to parents’ alma maters—or the long roster of private tutors, test prep centers, and college consulting agencies, tokens of privilege familiar within the affluent precincts of Bergen County. Particularly in Bergen County’s upper-middle-class culture, in which Ivies, not college, are the goal, and undergraduate studies are a tacit guarantee, many students end up falling victim to perfecting an elaborate but passionless script throughout high school to up their chances of admission.

On the topic of token work, Haeun says, “I don’t think it’s a bad thing that America’s educational system is sort of pressuring people to become more broad in their interests. Part of being in high school is to determine what you really want to do in life.”

“At the same time, though,” she qualifies, “I think it’s a real issue when people take a class or an extracurricular and don’t make the best out of it.”

For Haeun, there is a limited extent to which token work is morally allowable.

“There are plenty of people [at the places where I volunteer] that just do volunteering,” she observes, “and don’t really go that step above and beyond to be a good volunteer. They’re just there to get the volunteering hours. It’s a serious problem when things become just about the credit.”

“I think that you have to come to the point where you have to realize that it’s for your own good,” Raymond adds. “Once you realize that, [self-imposed expectations] come naturally to you.”

He seems to speak from experience. Raymond describes himself as someone who is keen to learn, and to learn in a sense that runs counter to the trappings of academic success that prevail in the current educational system. It’s why he gave up table tennis, baseball, and competitive piano, the latter of which he’d been playing since age five. It’s why he left the math team, science olympiad, and debate. It’s why he’s been without a smartphone, to say nothing of social media, for going on a third of a year, and why he upped, at the midpoint of his high school career, and booked it out of an elite magnet school in Greater New York.

“Maybe the reason why I couldn’t handle the stress was because of all the kinds of competitive stuff that I did,” Raymond suggests. He recalls spreading himself so thinly between musical extracurriculars, sports, and science competitions that the passion underpinning those pursuits tapered off, to the extent that he began to “view [them] as chores.”

“If your expectations aren’t self-imposed, then you’ll feel miserable every single step of the way,” Raymond reflects. “You’ll feel that everything you’re doing is because someone else is making you do it, and you lose sight of why you’re doing those in the first place.”

At this junction, with much on the line, the only fix was a deeply counterintuitive one. In hopes of revitalizing his enthusiasm for learning, Raymond would take drastic measures—namely, in dropping nearly all of his extracurricular commitments.

Ultimately, Raymond accepts the tradeoff.

“I think I’ll miss those things and I’ll do those things for fun,” he says, “but I think as of right now I should focus on other things.”

Raymond’s experience provides a microcosm of the crash-burn model that is magnified in senioritis. Although a prestigious schooling and a ream of commitments were, outwardly, markers of academic achievement, they had been more stultifying in effect.

Now, as a junior in the thick of things, Raymond notes that pressures have only sharpened, making it all the more important to establish a healthy mindset.

“Junior year is so crucial because this is the point where everything we do really does have an impact on our future,” he says. “This is the year where colleges will see the most; this is the year colleges will evaluate you [on], and that’s a lot of pressure.”

But this pressure to perform, he opines, has to be carefully tempered with a measure of self-examination.

“If you look amazing on your college application, but you didn’t learn anything, then I think you wasted a year,” Raymond says. “If you think that a good college application is worth your happiness at high school and your lack of learning for an entire year, then I think you have your values incorrect.”

The corrosion of student values is a fitting point of discussion, particularly when there are more expressly crooked ways in which the obsession with college rears its head.

“I’ve been noticing this more and more: there are people who are very interested in what other people are doing, and the level of privacy within our school is very [low,]” says George. He recalls an instance during the fall of 2019, in the midst of college applications season, in which he witnessed classmates “snooping around the guidance counselors’ mailboxes, looking through pink slips [transcript request forms] to see [which colleges] everyone else was applying to.

“That is not okay,” George says, “yet from what I’ve heard, a lot of people do it.”

These are the moral costs to the college craze.

When we shifted high school’s focus from learning to quantifiable academic achievement, we chained our means of internal validation to grade point averages, superscores, college names, and a tangle of other external metrics. The limited nature of these metrics encourages us to scheme against each others’ throats.

Over the course of high school, we have learned to iron out the creases in resumes, to finesse our essays, to arrange and shrewdly rearrange with artful hands. We have grown canny in our command of common-app-speak, but not in how to seek and tap into our passions. We have become well-versed in skills like regurgitation—memorizing the bare minimum to clinch an A, only to, post-exam, forget the same. We have trained a quick eye to clock an extracurricular commitment’s resume-building edge, but one that falters at discerning the potential to spark self-development. We’ve been taught the quick and dirty on all the wrong things.

But there are different strains of senioritis, it appears—some symptomatic of a more perilous ill, and some indicating personal ideological shifts, for better or for worse.

As a second-semester senior, Sarah finds that she still struggles with residual stressors that persist even after having run the brunt of the gauntlet. Periodically, she must remind herself to keep calm.

“I try to tell myself to relax a bit more,” she says, “and not stress about whether or not I got an A on my last exam or if I can be accepted to a certain college.”

Has this been working?

“Not until recently,” Sarah admits. “I’ve spent my entire high school career stressing over my grades and my academics in general that I never considered my mental health, and my social life always came second. Now I’ve learned that it’s not worth it.

“It’s not worth it to constantly stress and overwork and over-study,” Sarah adds. “Maintaining your grades is important, but if you get a B it’s not the end of the world. Take time to consider your friends because they’ll make you happy.

“Call it senioritis if you want,” says Sarah, “but I’m calling it keeping myself healthy.”

✶

It is like this sometimes—churlish and rude, butting in where it isn’t ever wanted.

It isn’t particular to the day of the week, to the state of our being, whether or not we’ve been sleeping or eating well. The email might ding, or it might come, though not often, through the mailbox first. If it hasn’t already played out in some iteration—college, program, or internship—it has outdone itself in our anticipatory imaginings: the killing ground. The scene of rejection.

And the aftermath—there is no stopping it. The prick of doubt—the hot-flash dread over the innocent inquiries tomorrow at school. The little voice, the sharp epiphany: oh. We are not good or not enough. There is just no coming back from that.

When confronted with academic anxieties, we might do well to stop ourselves softly and look the demon in the eye. To ask ourselves a few questions—like, what really decides prestige? And what does Guidance’s great whiteboard even measure?

✶

Much of America’s cultural sense of prestige is preordained, more or less, by a single and over-extolled gatekeeper: “Best National University Rankings”—the listicle published annually by the U.S. News & World Report—is taken as the definitive guide to top colleges. Such rankings must substantiate themselves in data. But numbers, we know, scarcely yield the whole picture. They don’t measure the intangibles for which extracurriculars were worked into the mix. There is a gaping flaw in the way we clock prestige.

The college acceptances charted on Guidance’s whiteboard don’t translate to Cresskill’s academic success, then—only to the luck of students who happened to be favored or slighted by the whims of a lottery-like process.

“There are so many people around here [in Bergen County] that have a 1570 SAT; a 1570 no longer is really anything special,” Haeun says. “Let’s say you have a 1570 SAT and you apply to, say, Harvard. Stats-wise, objectively speaking, the entire ‘holistic process’ that colleges talk about becomes meaningless at a certain point.” The unglamorous reality, she contends, is that past a certain threshold of scores, college admissions is more a lottery than a meritocracy.

“In that sort of environment,” Haeun adds, “what’s [college admissions] going to be based off of? The extra extracurricular that you did? The one volunteering experience that you did? No—it just really has to do with luck. Does the admissions officer have a particular affinity for like, volunteering with the mentally disabled versus volunteering with children.”

Raymond broadens this understanding to high school more generally. “Not just in college—in high school, too—you’ve got to accept that luck is a big part of the experience,” he says, “so if it turns out that things don’t work out, you’ve already done everything you could. And you have to learn to forgive yourself for that kind of stuff.

“As long as you can look at yourself at the end of day,” he decides, “and be like, ‘I did my best.’”

Haeun and Raymond find that this revelation—that so much of admissions, as well as academic success broadly, boils down to randomness and chance—can be a way into relieving some of the pressures of achievement. We haven’t been singled out for a doomed outcome, only subjected to the lurching caprices of a system run by deeply human admissions officers. In a system in which so many peers are clambering toward the same goalposts, and in which it’s become inconceivably difficult to distinguish oneself from the pack, rejection and failure are impersonal.

This is all to say outward metrics of success—namely, the admissions process—are a faulty groundwork on which to pin our self-worth. We know it well in our intuitions. We are uncomfortably familiar with the rollercoaster of small triumphs—an award, an A—and devastating lows—the stinging rejection emails, and, with a bit of lag, their snail-mail tautologies—and over its course, we have likely already gleaned a sense of this being the case. The college admissions process is a broken thing—warped by loopholes and shortcuts that only a few wield access to—and a crapshoot, too, given the staggering volume of students who apply to the few schools we’ve yoked to prestige.

Directly and implicitly, by the priorities it emphasizes, America’s educational culture disservices its students. The fixation around college admissions and other such external validations robs students of their health, puts them on false footing for self-discovery, and lays shaky foundations for their moral integrity.

We’ve seen its costs: the frenzy and the jaundice. The fight-or-flight anxiety, the scrambling, the reverb of emptiness in the final semester.

But there might be a way out, just as there was one in.

✶

We cannot bear ourselves, it seems. Our labored breath, our nascent tumors—our eyes are too bright. We come in with a particular set of assumptions about how to play the game. We have to go to sleep late—we have to compare and compete—we can but surrender to an inevitable trifecta. And so we do—we play the game. We greet each other with the number of hours we’ve slept, bicker a bit over who’s got it worse, share knowing smiles at the strain on our lungs and the full-body chills that ensue from lack of sleep. And so it goes, feeding into the expectation, eventually bowing to the assumption. Left unchecked, it stiffens. It tightens into more of a reality.

Evidently, we stake too much on achievements, which are subject to flux and fickle chance. If we stay in this mindset, we will always be in the service of things that may devastate us. We owe it to ourselves to be gentler on ourselves, and to reclaim the priorities of our education. To lean into emotion, to talk plainly about stress, but to remember that it all matters a little less than the neuroses would have us believe.

This is, to be sure, not to say that students don’t struggle with seriously concerning levels of stress. In a results-oriented academic culture that encourages validation through achievement and comparison, lofty expectations take a devastating toll on students’ mental health.

But to break the loop a little, the student body may do well to dismantle this way of thinking of wellness as a teetering triangle—demanding sacrifice, hell-bent on toppling—and to pick as many angles as it so desires.

Alternatively, we might think of it anew: as an array of concentric circles, happiness at the crux.

✶

This much we trust—the sun.

In its own time, the sun unscrews itself from its bloody socket. The shadows wane; the windows crack. We set back our clocks and tuck ourselves in. We pick three. We pick—and picking two exists only in bad dreams. We are, after all, not poised to die.

*Student has requested anonymity for privacy reasons.

If you are in crisis, please consider calling or texting the following numbers to speak with a trained crisis counselor. Calls are free of charge, confidential, and offered 24/7.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (toll-free) – Call 800-273-TALK (8255)

Crisis Text Line – Text NAMI to 741-741